Somaliland

Historic Flag Rises in Cardiff Castle: Somaliland’s Global Pride Reaches Welsh Skies

In a monumental show of solidarity, Cardiff Castle hosts Somaliland’s flag for the first time—sending a global message of recognition, resilience, and respect.

Somaliland’s flag rises above Cardiff Castle, Wales, in a landmark Independence Day celebration uniting diaspora, dignitaries, and cultural allies. A symbolic call to global leaders and investors.

For the first time in history, the red, white, and green flag of the Republic of Somaliland was raised high above one of Britain’s most iconic landmarks—Cardiff Castle—as a bold symbol of dignity, diaspora pride, and the unyielding march toward international recognition.

More than just a ceremony, this was a strategic diplomatic signal. With Welsh government officials, Cardiff Council dignitaries, and community leaders in attendance, the flag raising was a masterstroke of grassroots diplomacy—amplifying Somaliland’s presence on the world stage without needing permission from gatekeepers in Mogadishu or global corridors of power.

At exactly 12:30 PM, as the sun broke through the Welsh sky, the flag unfurled to cheers, traditional songs, and schoolchildren’s poetry. It was not just about the past—it was a blueprint for the future.

“This flag raising at Cardiff Castle is a proud and symbolic moment. It reflects our identity, our hopes for recognition, and our gratitude to Wales,” said Ali Abdi BEM, the community’s lead organiser.

Indeed, the Wales–Somaliland relationship is no accident. From health and education partnerships to cultural collaboration and language advocacy, Wales has long stood with Somalilanders in their quiet pursuit of self-determination. Today, that friendship is broadcast from a national monument.

This isn’t just a diaspora event—it’s a message to the world: Somaliland exists. Somaliland endures. Somaliland deserves recognition.

Every flagpole matters. Every castle wall that carries the Somaliland emblem becomes a soft power frontline in the battle for recognition. Cardiff Castle joins a growing list of international platforms—including Washington DC, London, and Oslo—where Somaliland’s case is being made by its people, not its proxies.

“Raising our flag in such a respected national landmark sends a powerful message of pride, resilience, and belonging,” said Abdikarim Adan, Director of the Wales Somaliland Community.

A Moment for Investors, Too

This global visibility is not just symbolic—it’s commercially strategic. With Somaliland unlocking billion-dollar energy and critical mineral reserves, every new flag raised around the world boosts its credibility in the eyes of cautious investors.

Somaliland’s real story isn’t just about the struggle for recognition—it’s about the rise of a secure, democratic, resource-rich African frontier waiting to be discovered.

WARYATV congratulates the people of Somaliland, the Wales Somaliland Community, and the leadership behind this historic ceremony.

This is not the end of the journey. It’s just the beginning.

Somaliland

Irro: Somali Unity Must Start Beyond Somaliland

Somaliland President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi Irro has said that calls for Somali unity are misplaced unless they first include other Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn of Africa, arguing that Somaliland’s status should only be discussed after those regions are unified with Somalia.

Speaking to Sky News Arabia, Irro said that if genuine Somali unity is the goal, then Djibouti, the Somali Regional State of Ethiopia, and Kenya’s Northeastern Frontier District should be part of that conversation first.

“If Somali unity is desired, Djibouti should join Somalia, it used to be part of it; the Somali Region of Ethiopia should not join Somalia; the NFD should not join. If the world wants Somali unity, they should unite,” Irro said, questioning why the union between Somalia and Somaliland is treated as unique.

He argued that many governments misunderstand Somali history, noting that Somali territories were divided into five parts during the 1884 Berlin Conference. Somaliland, he said, became the first Somali territory to gain independence in 1960 and was recognized by 35 countries, including Israel.

Irro said Somalilanders quickly rejected the union with Somalia after independence due to abuses and marginalization, making any future reunification impossible. “Another union is never possible,” he said.

Tensions between Somaliland and the Somalia federal government resurfaced late last year following Israel’s recognition of Somaliland, a move that angered leaders in Mogadishu.

Somaliland continues to push an international diplomatic campaign seeking formal recognition, insisting its case is rooted in history, sovereignty and the will of its people.

Opinion

The Unfinished Genocide: A Strategy Repeated

Mapping the Perpetual Threat: Foreign Intervention and the Siege of Somaliland’s Sovereignty.

By Mo Saeed

Introduction:

This report examines two distinct but thematically linked allegations concerning external military intervention in Somaliland. The first is a well-documented historical case: the hiring of foreign mercenary pilots by the Mohamed Siad Barre regime to conduct a brutal aerial campaign against Hargeisa and other northern cities in 1988–1989. The second is a contemporary genocide against Somaliland that the current Federal Government of Somalia is seeking military support from Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for similar purposes. This analysis aims to present the available facts, highlight potential parallels, and assess the implications of such external involvements.

The Historical Case:

Foreign Mercenaries in the 1988–1989 Bombing Campaign:

In May 1988, the Somali National Movement (SNM) launched a major offensive in northern Somalia (present-day Somaliland), capturing parts of Hargeisa as they could no longer watch Barre’s regime systematically wiping Isaq people out from the Horn of Africa . The Siad Barre regime responded with a massive and indiscriminate military campaign aimed at crushing the rebellion and terrorizing the civilian population, actions widely characterized as war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Isaaq genocide, also known as the Hargeisa Holocaust.

Recruitment and Origin of Pilots:

To supplement its air force, the Barre regime hired foreign mercenaries . These pilots were primarily recruited from South Africa and former Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

One specific account notes that “bombing raids on the towns for one month were conducted mainly by mercenaries recruited in Zimbabwe.

These mercenaries operated during the peak of the conflict in 1988–1989. They flew missions from the Hargeisa airport, targeting not only SNM positions but also conducting widespread, indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas in Hargeisa and surrounding regions. Their role was to provide the regime with additional aerial strike capacity for a campaign of collective punishment.

The objective was to support the Somali army in suppressing the civilians uprising by terrorising the civilian population through sustained aerial bombardment. This campaign resulted in the destruction of a large part of Hargeisa, Burao and caused thousands of civilian casualties, and is a central element of the planned and executed genocide against the Isaaq clan. The use of mercenaries allowed the regime to conduct this intense bombing campaign despite potential constraints within its own military.

Recent reports and statements indicate that the current Federal Government of Somalia is seeking direct military assistance from foreign states specifically Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for operations against Somaliland with the aim of committing genocide again past genocide survivors. A prominent fact is that Somalia’s Minister of Defence requested his Saudi counterpart to conduct airstrikes against Somaliland and to facilitate the capture of its president.

Turkey already has a significant military training and infrastructure presence in Somalia. The current evidence suggests this partnership could be expanded to include direct combat support.

Egypt and Saudi Arabia are being asked by Somalia to provide aerial military capabilities, reminiscent of the mercenary model used in 1988, though ostensibly through state-to-state agreements rather than private contracts.

Turkey has already deployed F-16 fighter jets to Somalia to be precisely part of this plan.

As of February 2026, these specific evidence of requests for bombing and capture operations reflect heightened tensions between Mogadishu and Hargeisa and a genuine fear in Somaliland of a return to large-scale, externally supported violence.

Historical Parallels:

The current requests evoke a direct parallel to the 1988 strategy, the Somali government seeking external aerial firepower to resolve its 60 year occupation with Somaliland. The historical precedent shows that such outsourcing of violence can lead to disproportionate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, with lasting humanitarian and political consequences.

Key Differences:

The historical case involved private mercenaries, while current evidence point to formal state actors.

The 1988 campaign occurred during the Cold War with less international scrutiny. Today, any such overt foreign military action would face immediate global attention and potential legal ramifications under international law.

Potential Implications:

For Somaliland this reinforces its deep-seated security fears and unhealed genocide scars and it could destabilize the relative peace maintained since the 1990s.

For Regional Stability, it could draw neighboring states into a proxy conflict, escalating tensions in the Horn of Africa.

For International Law, it would raise serious questions about the legality of cross-border military actions at the request of a government against a territory that has maintained de facto independence for decades and has legitimate and legal state continuity.

Conclusion:

The use of South African and Rhodesian mercenary pilots by the Siad Barre regime in 1988–1999 is a documented historical fact that exemplifies how external military capabilities can be harnessed for internal repression, resulting in atrocities. If Israel would not recognise Somaliland , Somalia was seeking support from Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia for assisting with their planned genocide.

The international community must remain vigilant to ensure that external military involvement, in any form, does not enable further human mainly by mercenaries recruited in Turkey, Egypt or Saudi Arabia.

This recurring threat of genocide from Somalia to Somaliland which is a de jure state underscore the critical need for the failed state of somalia respecting for international law and living peacefully with its neighbours to prevent any recurrence of the devastating genocide and violence witnessed by somaliland in the past.

Somaliland is not claiming a right to secede from a functioning state. it is reclaiming a pre-existing statehood after a failed merger. This makes its case sui generis.

By Mo Saeed

Somaliland legal research (SLR)

Somaliland

Somaliland President Attends State Dinner With UK Royal in Dubai

A UK royal, a key British MP, and Somaliland’s president at one table. This is diplomacy without permission — and it’s getting noticed.

DUBAI — President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi of the Republic of Somaliland and the delegation accompanying him in the United Arab Emirates attended an official state dinner in Dubai on Tuesday evening, marking another high-profile diplomatic moment for Somaliland on the international stage.

The dinner was attended by Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh, brother of King Charles III, underscoring the level of international engagement surrounding the Somaliland delegation during its working visit to the UAE.

Officials described the event as a reflection of the growing diplomatic visibility and international respect Somaliland is cultivating, particularly with longstanding partners such as the United Kingdom. Somaliland and Britain share deep historical ties dating back to the British Somaliland Protectorate era, a legacy that continues to shape political and social engagement between the two sides.

Also in attendance was Sir Gavin Williamson, a member of the UK House of Commons and one of the most vocal supporters of Somaliland’s quest for international recognition. Williamson has repeatedly raised Somaliland’s case in British and international political forums and is regarded in Hargeisa as a key ally.

President Abdullahi used the occasion to express his appreciation to Williamson for what he described as consistent and principled support for Somaliland and its people. According to Somaliland officials, the president emphasized the importance of allies who continue to advocate for Somaliland’s democratic record, stability, and right to self-determination.

Discussions during the event highlighted the shared interest in strengthening cooperation across governance, development, security, and people-to-people relations. Participants also reaffirmed a mutual commitment to dialogue, peaceful coexistence, and international cooperation as foundations for future engagement.

The dinner forms part of a broader diplomatic push by Somaliland’s leadership during the UAE visit, as President Abdullahi seeks to expand international partnerships and reinforce Somaliland’s image as a stable, responsible political actor in the Horn of Africa.

Officials said the engagement once again demonstrated Somaliland’s growing confidence and effectiveness in international diplomacy, particularly in strengthening ties with traditional partners such as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Somaliland

Somaliland President Returns to World Governments Summit

Second year in a row, Somaliland speaks where global power listens.

DUBAI — President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (Irro) has once again placed Somaliland on a major global stage, participating for the second consecutive year in the World Governments Summit, currently underway in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

The summit, one of the world’s most influential international gatherings, brings together heads of state, prime ministers, senior ministers, global policy experts, business leaders, and international organizations to debate modern governance, leadership, innovation, and long-term state development. Its agenda is designed not around ceremony, but around how power is exercised, institutions are built, and states adapt to an increasingly volatile global order.

Irro’s repeat presence is significant. In diplomatic terms, continuity matters. Returning to the summit for a second year signals that Somaliland is no longer seeking visibility as a one-off gesture, but is positioning itself as a consistent participant in high-level global conversations. For an unrecognized state, repetition is leverage.

According to officials accompanying the delegation, President Irro is expected to hold a series of bilateral meetings with international leaders and senior officials on the margins of the summit. Those discussions are set to focus on development cooperation, stability, investment, and Somaliland’s long-term national vision—areas that align closely with the summit’s emphasis on future-oriented governance.

The diplomatic undertone of the visit is impossible to miss. Somaliland’s participation last year reportedly angered the federal government in Mogadishu, which objected to the invitation and, according to regional diplomatic sources, raised concerns with the United Arab Emirates in an effort to prevent a repeat appearance. Those efforts failed.

Relations between Mogadishu and Abu Dhabi have since deteriorated further, particularly after Somali officials accused the UAE of quietly supporting Somaliland’s recognition drive—an allegation Emirati authorities have not publicly endorsed but have also not forcefully denied. Against that backdrop, Irro’s presence in Dubai this year carries a sharper geopolitical edge.

For Somaliland, the summit offers more than symbolism. It provides a platform to present its record on peacebuilding, democratic processes, and state-building to an audience that increasingly values stability and governance capacity over formal diplomatic labels. In a world where influence is often shaped by access rather than recognition alone, Somaliland is choosing presence as its strategy.

By returning to the World Governments Summit, Irro is reinforcing a clear message: Somaliland intends to be seen, heard, and engaged—regardless of who objects.

Somaliland

President Irro Heads to UAE for World Governments Summit in Dubai

From Hargeisa to Dubai—Somaliland steps into a room of 130 nations and speaks for itself.

The President of the Republic of Somaliland, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (Irro), has departed for the United Arab Emirates on a high-profile working visit that underscores Somaliland’s expanding diplomatic footprint, as he prepares to participate in the World Governments Summit in Dubai.

The visit carries significant diplomatic weight. At the summit, President Irro will represent Somaliland at one of the world’s most influential global forums, bringing together leaders and senior officials from more than 130 countries, alongside international organizations and global decision-makers shaping political and economic agendas.

According to officials, President Irro is expected to deliver a keynote message highlighting Somaliland’s experience in state-building, peace consolidation, democratic governance, and development. The address is aimed at positioning Somaliland as a stable and credible political entity in the Horn of Africa, while reinforcing its role as a responsible partner in a region often defined by instability.

Beyond the summit’s formal sessions, the President and his delegation are scheduled to hold a series of bilateral meetings with international leaders and senior officials. These discussions will focus on priority areas for Somaliland, including development cooperation, investment opportunities, trade expansion, security collaboration, and long-term strategic partnerships.

The government views the invitation and participation in the World Governments Summit as another signal of growing international confidence in Somaliland’s governance model. Despite the absence of formal international recognition, Somaliland continues to secure a presence in high-level global forums, leveraging its record of peace, political continuity, and institutional development.

Officials in Hargeisa say the UAE visit reflects a broader strategy by the Irro administration to deepen international engagement, attract investment, and translate Somaliland’s internal stability into tangible economic and diplomatic gains.

As global leaders gather in Dubai to debate governance, technology, and future development models, Somaliland’s presence at the table serves as a reminder that influence in international politics is increasingly shaped not only by recognition, but by performance, credibility, and the ability to articulate a compelling national story.

Somaliland

How Turkey Helped Block Somaliland’s Recognition

Turkey’s Admission and Somaliland’s Long Road to Recognition: What Davutoğlu’s Words Reveal?

For years, Somalilanders have argued that their lack of international recognition is not the result of ambiguity about their record, but of deliberate geopolitical obstruction. This week, that claim received rare and explicit confirmation—from Ankara itself.

Former Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu publicly acknowledged that in 2012 he personally intervened to block a European Union initiative, led by the United Kingdom, that aimed to recognize Somaliland as an independent state. His account offers one of the clearest windows yet into how Somaliland’s diplomatic trajectory was halted—not by doubts over its governance, but by regional politics and unrelated strategic calculations.

According to Davutoğlu, the push for recognition was already gaining momentum when he arrived at a meeting with European leaders. At its center was William Hague, then Britain’s foreign secretary, who argued that Somaliland’s stability, democratic credentials, and internal security set it apart from the chaos engulfing southern Somalia at the time. By any conventional benchmark, Hague’s case was straightforward: Somaliland functioned as a state, while Somalia barely did.

Davutoğlu rejected that logic outright. In his telling, recognizing Somaliland would “divide” Somalia just as Turkey claimed to be helping stabilize it. More strikingly, he framed the issue through a lens that had little to do with the Horn of Africa. Recognition of Somaliland, he warned, could open the door for Britain to recognize Northern Cyprus—a red line for Turkey. The comparison stunned those in the room, but it proved decisive.

In that moment, Somaliland’s future was subordinated to Ankara’s Cyprus policy.

Dialogue as Delay

Davutoğlu went further, describing how Turkey then positioned itself as a mediator between Hargeisa and Mogadishu. He called both Somaliland’s then-president Ahmed Mohamed Mahmoud (Siilaanyo) and Somalia’s transitional leader Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, urging them to engage in talks under a banner of Muslim solidarity and non-interference by external powers.

Those talks, which dragged on for more than a decade, never produced a settlement. For many in Somaliland, Davutoğlu’s admission confirms what they long suspected: the dialogue process was not a bridge to recognition, but a holding pattern designed to freeze it. As long as talks existed, international actors could claim the issue was “under discussion” and postpone decisive action indefinitely.

History appears to support that view. While Somaliland maintained relative peace, held elections, and built institutions, the international community waited. Recognition was deferred not because Somaliland failed, but because it was asked to keep talking.

From Mediation to Confrontation

That era is now over. Talks between Hargeisa and Mogadishu have collapsed, and relations have sharply deteriorated. Somaliland has accused the Federal Government of Somalia of undermining its sovereignty, particularly through involvement in new regional administrations in contested areas. Mogadishu, for its part, has formally labeled Somaliland a security threat—placing “secessionist ideology” just behind terrorism in its national threat assessment.

The symbolism is hard to miss. Dialogue once used to block recognition has ended, but the political damage remains.

Against this backdrop, Somaliland achieved a historic breakthrough last December, when Israel became the first United Nations member state to formally recognize it. Whether others will follow remains uncertain. But Davutoğlu’s remarks have reframed the debate.

They confirm that Somaliland’s case was not lost in the shadows of diplomacy. It was actively set aside.

A Lesson From the Past

For Somalilanders, the significance of Davutoğlu’s admission lies less in assigning blame than in clarifying history. Recognition did not fail because Somaliland lacked legitimacy. It failed because powerful states chose stability narratives, regional bargains, and unrelated disputes over the principle of self-determination.

That clarity matters now. As Somaliland presses its case anew, it does so with a documented record—not only of its own governance, but of the decisions that denied it recognition in the past.

History, it turns out, was not silent. It was interrupted.

Somaliland

Somaliland Pushes Elections Back by Ten Months

Somaliland Delays Parliamentary and Local Elections, Citing Drought, Security and Political Disputes.

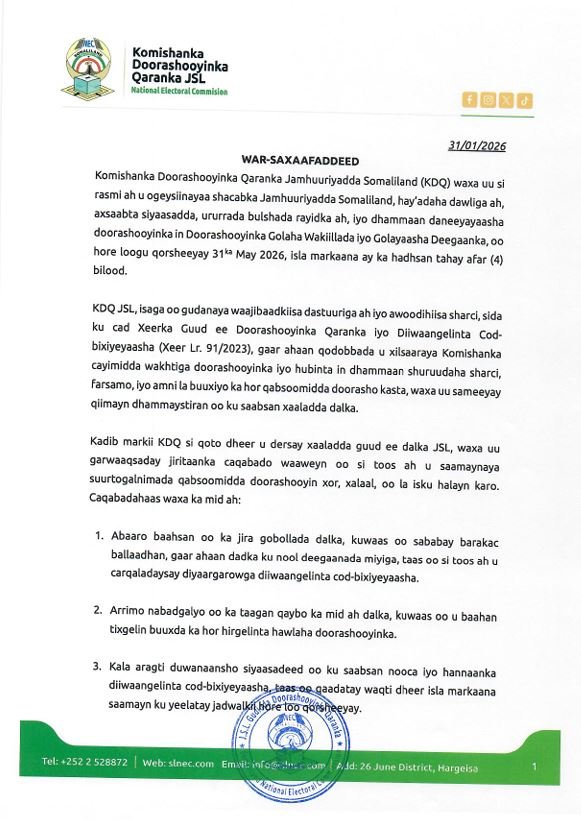

The Somaliland Electoral Commission’s decision to postpone the House of Representatives and Local Government elections marks a critical moment for the country’s democratic trajectory. Scheduled for May 31, 2026, the vote has now been pushed back by ten months, a move the Commission says is driven not by political convenience but by hard constraints on the ground.

At the center of the decision is a convergence of pressures that have become increasingly difficult to manage simultaneously. Prolonged drought has disrupted large swathes of the country, affecting population movement, livelihoods and the basic logistics required for voter registration and polling. In parallel, localized security challenges have raised concerns about the Commission’s ability to guarantee safe access to polling stations and election materials in all regions.

Political disagreements have compounded those challenges. While the Commission did not specify the nature of the disputes, the reference reflects a familiar pattern in Somaliland politics: unresolved tensions over process and timing that can undermine confidence if elections proceed without broad consensus.

By invoking its constitutional mandate under the General Elections and Voter Registration Act, the Commission is attempting to anchor the postponement firmly in law. The language of the statement is deliberate. This is presented as a “special extension,” not an open-ended delay, and as a measure designed to protect the integrity of the vote rather than suspend it.

The ten-month extension creates a narrow but consequential window. During this period, the Commission says it will complete outstanding technical work on voter registration, finalize election materials, and strengthen operational readiness. In effect, it is buying time to ensure that when elections do take place, they meet both domestic constitutional standards and international expectations of credibility.

Still, the decision carries political risk. Election delays, even when legally justified, can feed public suspicion in a region where democratic processes are often under strain. For Somaliland, which has long presented itself as a relative democratic exception in the Horn of Africa, maintaining public trust is as important as managing logistics.

The Commission appears acutely aware of that balance. Its emphasis on legality, transparency and accountability is aimed at preempting accusations that the delay serves partisan interests. Whether that assurance holds will depend less on words than on visible progress during the extension period.

The next ten months will therefore function as a test. If the Commission uses the time to deliver tangible improvements in voter registration, security coordination and political dialogue, the postponement may ultimately strengthen Somaliland’s democratic institutions. If progress stalls, the delay could deepen skepticism and sharpen political competition.

For now, the message from the Electoral Commission is clear. The cost of proceeding under unfavorable conditions is judged to be higher than the cost of waiting. Somaliland is choosing caution over speed, betting that credibility is better preserved by delay than by a flawed vote.

Somaliland

How Irro Is Engineering Somaliland’s Moment of Recognition

Irro’s Cabinet Signals Governance Shift as Somaliland Moves From Recognition Campaign to Statecraft.

Inside the Somaliland Presidential Palace in Hargeisa, the 52nd session of the Council of Ministers carried a tone markedly different from past cabinets shaped by diplomatic aspiration. This was not a government pleading for acknowledgment, but one organizing itself to wield it.

Presiding over the meeting, President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (Irro) convened a cabinet that increasingly resembles a state preparing for sustained international engagement. The agenda was sober and technical: internal security, fiscal discipline, institutional coordination, and public communication. These are not the rituals of symbolic politics. They are the mechanics of sovereignty.

The security briefing set the tone. Interior and National Security Minister Abdalla Mohamed Arab described Somaliland as secure “at all levels,” but introduced a notable recalibration in language. Diplomatic progress, he warned, has expanded Somaliland’s circle of adversaries. Recognition, in this framing, is not an endpoint but a multiplier of risk. The call for tighter cooperation between institutions and citizens reflects an administration that sees internal cohesion as the first line of defense for external legitimacy.

If security is the shield, finance is the engine. Finance Minister Abdullahi Hassan Adan reported that January 2026 revenue targets are being met—an early but essential signal to international partners assessing Somaliland’s economic credibility. More consequential than the figures themselves was the rollout of a unified government accounting system. By standardizing financial records across ministries and training staff through the National Institute of Accounting, the Irro administration is moving to dismantle the fragmentation that has long undermined state efficiency.

This push is inseparable from Somaliland’s economic spine: the Berbera corridor. Continued expansion of the port, in partnership with DP World, remains the centerpiece of national economic strategy. In cabinet discourse, Berbera is no longer just infrastructure—it is leverage, anchoring Somaliland’s relevance to Red Sea trade and regional supply chains.

Beyond hard security and finance, the session addressed the quieter infrastructures that sustain statehood. Education Minister Ismail Duale Yusuf outlined preparations for the 8th Joint Education Sector Review, emphasizing equitable access and modern technology. The message was clear: recognition without human capital is hollow.

Health Minister Dr. Hussein Bashir Hirsi detailed a rapid response to fever outbreaks in multiple regions, deploying medicines and medical personnel. The subtext was unmistakable—state capacity must be visible not only in diplomacy, but in emergencies that test public trust.

Regional balance emerged as another strategic priority. Minister Kaltun Sh. Hassan Abdi introduced a Regional Development Framework aimed at ensuring that the dividends of recognition reach beyond Hargeisa. In a political system where marginalization can quickly become destabilizing, balanced development is not charity; it is risk management.

Perhaps the most revealing intervention came from Minister of the Presidency Khadar Hussein Abdi, who pressed for a “unified voice” across government. In a media environment saturated with misinformation, the administration plans structured communication training for senior officials. This is not about spin. It is about narrative discipline at a moment when contradictions can be exploited by opponents of Somaliland’s statehood.

As the session closed, President Irro returned to first principles. Recognition, he said, is a national goal rooted in self-determination—but it must be defended through competence. Accounting systems, regional planning, crisis response, and message coherence are now instruments of diplomacy.

The signal from the 52nd Council of Ministers was unmistakable. Somaliland is no longer merely arguing that it deserves recognition. Under Irro, it is behaving like a state that expects to be judged by how it governs once it has it.

-

Interagency Assessment2 months ago

Interagency Assessment2 months agoTOP SECRET SHIFT: U.S. MILITARY ORDERED INTO SOMALILAND BY LAW

-

Somaliland4 months ago

Somaliland4 months agoSomaliland Recognition: US, UK, Israel, and Gulf Bloc Poised for Historic Shift

-

Minnesota1 month ago

Minnesota1 month agoFraud Allegations Close In on Somalia’s Top Diplomats

-

Middle East2 months ago

Middle East2 months agoSaudi Arabia vs. UAE: How The Gulf Rivalry is Heating Up

-

American Somali3 months ago

American Somali3 months agoWhy Frey Won a Significant Share of the Somali Vote Against a Somali Opponent

-

Middle East2 months ago

Middle East2 months agoTurkey’s Syria Radar Plan Triggers Israeli Red Lines

-

Editor's Pick1 month ago

Editor's Pick1 month agoWhy India Is Poised to Become the Next Major Power to Recognize Somaliland

-

The Million-Follower Exile2 months ago

The Million-Follower Exile2 months agoWhy America Deported Its Most Famous Somali TikTok Star And Who Paid The Price