Somalia

How do you solve a problem like Somalia?

This Thursday, the great and the good will descend on London to discuss Somalia, a country that has topped the Fragile States Index for eight of the past 10 years.

The London Somalia Conference, co-chaired by the UK, Somalia and the United Nations, will be held in Lancaster House, a grand mansion in the exclusive district of St James’s. Many of the delegates will stay in swish hotels nearby.

This is the third such London gathering since 2012, and there is an element of “cut and paste” to its agenda, which focuses on security, governance and the economy.

The official conference document emphasizes how much progress has been made.

But its description of Somalia from the time of the first meeting still applies: “Chronically unstable and ungoverned”, and threatened by Islamist militants, piracy and famine.

Piracy, which at its height cost $7bn (£5.4bn) a year, is much diminished, although there has been a recent resurgence.

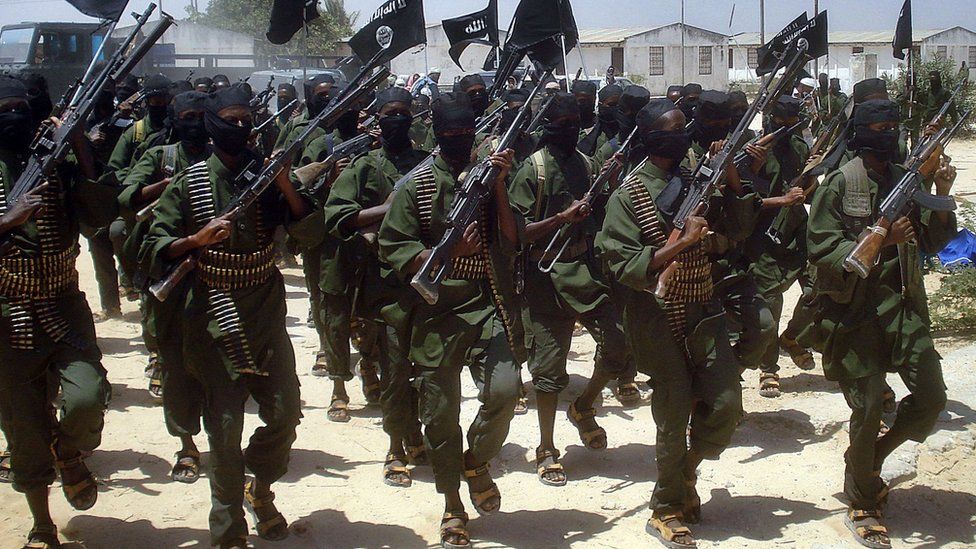

US drones, African Union troops, Western “security advisers” and Somali forces have pushed al-Shabab from most major towns, although the jihadists still control many areas and attack at will.

A recent electoral process resulted in a new and – for the time being – popular president, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, nicknamed Farmajo, and more female and youth representation in parliament.

Life-threatening malnutrition

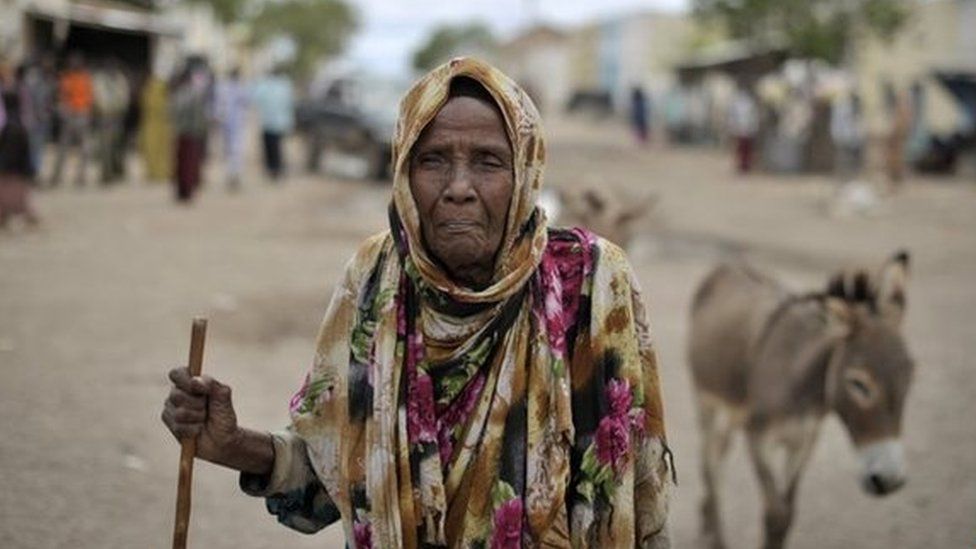

Somalia is in a “pre-famine” stage rather than the full-blown disaster of 2011, in which more than 250,000 people died.

But it is perhaps surprising that the current water shortage will not be a headline topic at the conference.

The country is in the grip of its worst drought in decades. Four successive rainy seasons have failed.

One boy, dressed in purple, stares blankly at the wall. “His brain is damaged due to a prolonged lack of adequate nutrition,” says Dr Yusuf Ali, who returned home to Somalia from the UK two years ago. “He will never recover.”

According to UNICEF, the number of children who are or will be acutely malnourished in 2017 is up by 50% from the beginning of the year, to a total of 1.4 million, including 275,000 for whom the condition is or will be life-threatening.

Most are too sick to go to school or help herd animals, making the life of the country’s many nomads even more precarious.

People are already dying from hunger and diseases that strike those weakened by lack of food.

Severely malnourished children are nine times more likely than healthy ones to die from illnesses such as measles and diarrhoea.

The World Health Organization says there were more than 25,000 cases of cholera in the first four months of 2017, with the number expected to more than double to 54,000 by June.

More than 500 people have already died from the disease.

It is not just humans who are suffering.

‘Triangle of death’

In Somaliland, officials say, 80% of livestock have died.

Livestock is the mainstay of the economy – the ports in Somaliland and nearby Djibouti export more live animals than anywhere else in the world, mainly to the Gulf.

In south-western Somalia, tens of thousands of drought-affected people have fled to Baidoa, clustering into flimsy, makeshift shelters on the outskirts of the city.

This area – known as the “triangle of death” – was the epicentre of the famines of 2011 and 1991.

“Al-Shabab is harvesting the boys and men we left behind on our parched land, offering them a few dollars and a meal,” says one woman. “Against their will, our children and husbands have become the jihadists’ new army.”

“The biggest problem in dealing with this drought is insecurity,” says Sharif Hassan Sheikh Aden, president of South West State, in his modest palace in Baidoa.

The city, which is protected by a ring of Ethiopian troops, is right in the heart of al-Shabab country. “The militants have closed all the roads so we cannot deliver help to those who need it most.”

Deadly clashes

This brings home in the starkest of terms why security is top of the London Somalia Conference agenda.

As long as Somalia remains violent, with different parts of the country controlled by a multitude of often conflicting armed groups, it will be impossible to deliver emergency assistance, let alone long-term development.

The recently created South West State is one of the regions making up the new federal Somalia.

Critics fear this will lead to balkanization, and risks introducing another dimension to conflict, as the new states rub up against each other and start fighting. This has already happened in central Somalia, where last year there were deadly clashes between Puntland and Galmudug states.

The attitude of people in South West State shows how much of a gamble the federal system is.

“We have always been marginalized and looked down on by other Somalis,” says a farmer, Fatima Issa.

“We do not want the federal troops here. They don’t hunt down al-Shabab the way our local militias do. We should push for more autonomy, maybe even break away and declare independence like Somaliland did in 1991.”

One aim of the London Somalia Conference is to push for more progress on the sharing of resources between the regions and the center. This contentious issue has been debated since before the first London gathering in 2012.

‘Predatory carnival’

South West State has a special friendship with Ethiopia, which is not on the best of terms with the new federal government. This highlights another possible problem – some foreign powers have started to sign bilateral agreements with regional states.

For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is building a military base in Somaliland, a territory the federal government considers an integral part of Somalia. The UAE has also given military hardware to Jubaland State in southern Somalia.

Somalia’s former special envoy to the US, Abukar Arman, has described the London Somalia Conference as a “predatory carnival”, with foreign powers gathering to slice up Somalia for their own benefit.

Some in Somalia see it as a waste of time.

“It is an expensive talking-shop,” says Ahmed Mohamed, a rickshaw driver in the capital Mogadishu. “The politicians and diplomats are obsessed with the conference instead of taking action on the drought.”

But lessons have been learned, and there is now a far more nuanced approach to Somalia than there was when the crisis began, in the late 1980s.

The US response to the Somali famine of 1991 was to send in nearly 30,000 troops. This ended in a humiliating withdrawal, following the shooting down of two US Black Hawk helicopters in 1993.

Now, much of the talk is of “Somali-owned” processes, although the shadows of a growing number of foreign powers can be seen lurking in the background.

Africa

EU Tightens Schengen Visa Rules for Somali Nationals

The European Union introduces stricter Schengen visa regulations for Somalia to improve readmission cooperation. Changes include single-entry visas, higher fees, and longer processing times.

In a decisive move, the European Union Commission has proposed stringent new visa regulations for Somalia. This initiative aims to enhance cooperation on the readmission of Somali nationals who have entered and stayed in the EU without proper documentation. The proposed changes, pending EU Council approval, include issuing only single-entry visas, increasing visa fees, and extending application processing times from 15 to 45 days. Additionally, the EU may suspend certain regulations requiring the submission of supporting documents for visa applications.

“Despite steps taken by the EU and its Member States to improve readmission cooperation, Somalia’s efforts remain insufficient,” the EU Commission declared. This proposal forms part of the EU’s broader strategy to manage irregular migration within its borders by ensuring countries cooperate on the readmission of their nationals.

The EU has implemented similar measures against other countries, such as Ethiopia and The Gambia. In April, multiple-entry Schengen visas were halted for Ethiopians, and visa fees were increased for Gambian nationals, although the fee hike was later revoked. Other measures against The Gambia remain in place.

The Commission’s statement noted that the proposal would soon be presented to the EU Council, where member states will decide on the next steps. This move underscores the EU’s firm stance on managing migration and ensuring compliance with readmission agreements.

Analysis

Beauty in the Crossfire: Miss Somalia Pageant Amid Violence

Amid Explosions and Controversy, Somali Women Defy Odds in Groundbreaking Beauty Pageant

On a night when most of Somalia tuned in to the Euro football final, a very different kind of spectacle unfolded at Mogadishu’s Elite Hotel. Hundreds gathered to witness the Miss Somalia pageant, a daring celebration of beauty and resilience in one of the world’s most dangerous places to be a woman. Just a kilometer away, the grim reality of Somali life was underscored by a car bomb explosion that killed five and injured twenty. The militant group al-Shabab, notorious for its reign of terror over Somalia, claimed responsibility for the attack.

The juxtaposition of a beauty pageant with such violence highlights the schizophrenic nature of life in Somalia. While pageant contestants paraded in glamorous gowns, the nearby explosion shattered the night, a stark reminder of the pervasive threat of terrorism. This contrast paints a vivid picture of a nation grappling with its identity and future.

Hani Abdi Gas, founded the competition in 2021. In a country where Islamist militants and conservative traditions dominate, her initiative is nothing short of revolutionary. Gas, who grew up in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya before returning to Somalia in 2020, sees the pageant as more than a beauty contest. It’s a platform for lifting women’s voices, fostering unity, and empowering Somali women.

Gas believes that Somalia, long deemed one of the worst places to be a woman, is ready to join the rest of the world in celebrating female beauty and aspiration. “I want to celebrate the aspirations of women from diverse backgrounds, build their confidence, and give them a chance to showcase Somali culture worldwide,” she said.

This year’s contestants reflected this diversity. Among them was a policewoman, a powerful symbol of women breaking barriers in a traditionally male-dominated society. However, not everyone was pleased. Many Somalis view beauty pageants as affronts to their culture and religion. Clan leader Ahmed Abdi Halane expressed disgust, saying, “Such things are against our culture and our religion. If a girl wears tight clothes and appears on stage, it will bring shame upon her family and her clan. Women are supposed to stay at home and wear modest clothes.”

Some women also oppose the pageant. Sabrina, a student, criticized the contestants for appearing in public without covering their necks, saying, “It is good to support the Somali youth but not in ways that conflict with our religion.”

Despite these criticisms, the pageant proceeded with its vibrant display of Somali culture. Aisha Ikow, a 24-year-old university student and make-up artist, was crowned Miss Somalia, taking home a $1,000 prize. Ikow, representing South-West state, vowed to use her platform to combat early marriage and promote girls’ education. “The competition celebrates Somali culture and beauty while shaping a brighter future for women,” she said.

The judging panel, which included Miss Somalia 2022 and a representative from the Ministry of Youth, found it hard to choose a winner. They assessed contestants on physical beauty, public speaking, and stage presence. An online vote, costing $1 per vote, funded the event and future international pageant participation.

The glitzy event in a luxury hotel contrasted sharply with the harsh realities faced by most Somali women. Four million Somalis, a quarter of the population, are internally displaced, with up to 80% being women. The UN ranks Somalia near the bottom on the Gender Inequality Index, with alarming rates of gender-based violence and female genital mutilation. Traditional practices still dictate that a rapist must marry his victim, and legal protections for women are severely lacking.

Despite these challenges, the Miss Somalia pageant signifies a slow but significant change. The fact that such an event could be held in Mogadishu, even amid nearby violence, indicates a shift in societal attitudes and an improvement in security.

The crowd at the Elite Hotel stayed until the early hours, undeterred by the attack’s proximity. They were engrossed in the pageant, the sound of the explosion drowned out by the waves crashing on the nearby beach.

In a nation torn by conflict and conservative values, the Miss Somalia pageant stands as a beacon of hope. It is a testament to the resilience of Somali women and their determination to carve out spaces of empowerment and celebration. As Somalia continues to navigate its complex identity, events like these are crucial in shaping a more inclusive and progressive future.

Kiin Hassan Fakat, reporting with Bilan Media, and Mary Harper, author of two books on Somalia, provide a lens into this transformative moment, capturing the courage and aspirations of Somali women amidst a backdrop of turmoil.

Editor's Pick

ATMIS Withdrawal Sparks Concerns Among East African Leaders

President Museveni and President Ruto Warn of Increased Insecurity Amid Al-Shabaab Resurgence

By Kasim Abdulkadir:

Uganda and Kenya express concerns over the planned ATMIS troop withdrawal from Somalia, citing rising terrorism threats and regional instability.

The scheduled departure of ATMIS troops from Somalia has raised significant alarm among regional leaders, notably Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and Kenyan President William Ruto. The two leaders, whose countries contribute troops to ATMIS, voiced their concerns during a recent meeting in Nairobi. They emphasized the potential security vacuum that could be exploited by terrorist groups like Al-Shabaab, thus threatening regional stability.

The United Nations Security Council’s withdrawal plan involves removing 4,000 ATMIS troops by the end of June, following the departure of 5,000 troops last year. This downsizing has reportedly allowed Al-Shabaab to reclaim substantial territories, undermining recent military gains by Somali forces.

President Ruto and President Museveni

President Ruto highlighted that both he and President Museveni agree on the necessity of aligning the troop reduction with the security conditions in Somalia. Analysts and security experts have echoed these concerns, arguing that Somalia’s military is not yet equipped to maintain control over the reclaimed areas.

Abdisalan Guled, a former deputy security chief in Somalia, warned that the withdrawal could jeopardize the significant strides made against Al-Shabaab. He noted that central and southern Somalia remain hotspots for extremism, with numerous incidents reported in regions like Galmudug and Hirshabelle.

International partners, including the European Union, have also expressed apprehension. They caution that the Somali National Army (SNA) lacks the capacity to assume full security responsibilities, urging a reconsideration of the withdrawal timeline.

Since its inception nearly 17 years ago, ATMIS (formerly AMISOM) has played a crucial role in stabilizing key areas of Somalia, including the capital Mogadishu. Despite criticisms over its inability to decisively weaken Al-Shabaab, ATMIS has been instrumental in maintaining a semblance of order and security.

Security expert Farah Ow Osman supports the Somali government’s request to delay the ATMIS withdrawal, arguing that an extension would provide Somali forces the necessary time to strengthen their position against Al-Shabaab. He suggests that this delay could potentially be endorsed by the United Nations Security Council, ensuring a smoother transition and sustained stability in Somalia.

The departure of ATMIS troops presents a significant challenge to the region’s security landscape. With Al-Shabaab poised to exploit any gaps left by the withdrawal, the concerns raised by Presidents Museveni and Ruto underscore the need for a carefully managed and strategically timed exit to prevent a resurgence of violence and instability. The coming months will be crucial in determining whether the gains made against terrorism in Somalia can be preserved and built upon.

Somalia’s Shift Towards Russia: Strategic Realignment or Desperate Gamble?

Analysis

Somalia’s Shift Towards Russia: Strategic Realignment or Desperate Gamble?

Exclusive Insights into Somalia’s Strategic Shift and Its Global Implications

By Kasim Abdulkadir:

Explore the emerging Somalia-Russia alliance, the factors driving Somalia to sever Western ties, and the potential global consequences of this geopolitical shift.

Somalia’s recent diplomatic maneuvers signal a significant shift in its international alliances, with President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud engaging in strategic discussions with Russian Ambassador Mikhail Golovanov. As Somalia prepares to sever its ties with Western countries and the United Nations, this evolving relationship with Russia raises crucial questions about the underlying motives, key players, and potential consequences for both nations and the broader geopolitical landscape.

Historical Context and Motivations

Somalia, plagued by decades of violence, corruption, and political instability, has long relied on Western aid and the United Nations for support. Despite this, the country remains mired in poverty and conflict, with militant groups like Al-Shabab exploiting the power vacuum left by a dysfunctional government. The recent intelligence reports suggesting Somalia’s intention to cut ties with Western allies and the UAE indicate a dramatic reorientation of its foreign policy.

Russia’s interest in Somalia is not surprising, given its historical strategy of expanding influence in Africa through diplomatic and economic initiatives, military cooperation, and resource extraction. The Kremlin’s pursuit of Somalia’s vast natural resources, including minerals, oil, and gas, aligns with its broader goal of challenging Western dominance and establishing strategic footholds in resource-rich regions.

The Key Players and Their Interests

President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s administration appears determined to pivot towards Russia, motivated by a mix of dissatisfaction with Western support and the allure of new economic opportunities. The president’s gratitude towards Russia for its role in Somalia’s HIPC debt relief process suggests a deeper appreciation and trust in Russian support.

Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia has intensified its engagement with African nations, seeking to expand its geopolitical influence. By offering economic and military support to Somalia, Russia aims to secure access to crucial resources and establish a strategic presence in the Horn of Africa, a region critical for global maritime trade routes.

The United States, European Union, and United Nations have been the primary supporters of Somalia’s reconstruction efforts. However, their influence is waning as Somalia gravitates towards Russia. The potential withdrawal of UNSOM and AMISOM highlights the fragility of Western-led stabilization efforts in the region.

Potential Consequences and Implications

Russia’s engagement in Somalia promises lucrative economic opportunities, particularly in resource extraction. Access to Somalia’s minerals, oil, and gas can bolster Russia’s energy sector, enhancing its global market position. However, these ventures come with significant risks, including security challenges posed by militant groups and the instability of Somalia’s political landscape.

Somalia’s pivot towards Russia signifies a broader realignment of global alliances, challenging Western hegemony in Africa. This shift could inspire other African nations to reconsider their alliances, potentially leading to a multipolar world order where regional powers like Russia and China play more dominant roles.

The withdrawal of Western support could exacerbate Somalia’s security challenges. Without the stabilizing presence of AMISOM and the strategic guidance of UNSOM, Somalia risks descending further into chaos, providing fertile ground for militant groups to expand their influence.

Somalia’s humanitarian situation remains dire, with millions in need of aid. Russia’s focus on strategic and economic interests may not adequately address these humanitarian needs, potentially worsening the plight of Somalia’s most vulnerable populations.

Expert Insights and Data-Driven Analysis

Experts suggest that Somalia’s shift towards Russia is driven by a combination of economic desperation and political opportunism. Dr. Ahmed Abdullahi, a Somali political analyst, notes, “The Somali government’s frustration with the slow pace of progress under Western aid programs has made the allure of Russian support irresistible. However, this move is fraught with risks, as Russia’s track record in supporting fragile states is mixed at best.”

Data from the World Bank and other financial institutions highlight the precarious state of Somalia’s economy, with unemployment rates soaring and infrastructure in dire need of investment. The promise of Russian investment in these sectors could offer a lifeline, but the long-term benefits remain uncertain given the volatile political environment.

Historical Parallels and Lessons

Historical parallels can be drawn with other African nations that have shifted their alliances in search of new opportunities. The Democratic Republic of Congo’s engagement with China, for instance, brought substantial investment but also raised concerns about resource exploitation and environmental degradation. Somalia must navigate these challenges carefully to avoid similar pitfalls.

Future Developments and Recommendations

Looking ahead, Somalia’s relationship with Russia will likely evolve based on several factors:

For Somalia to benefit from Russian engagement, it must strengthen its governance structures and ensure that investments are managed transparently and equitably. This requires a concerted effort to combat corruption and build institutional capacity.

Somalia should strive for a balanced foreign policy, maintaining constructive relations with both Eastern and Western powers. This approach can maximize the benefits of international support while mitigating the risks of overreliance on a single partner.

Engaging with neighboring countries and regional organizations will be crucial for Somalia’s stability and development. Collaborative security arrangements and economic partnerships can enhance regional stability and create a more conducive environment for investment.

Somalia’s youthful population and increasing connectivity present opportunities to harness technology for development. Investments in digital infrastructure and education can empower the next generation and drive economic growth.

In conclusion, Somalia’s evolving relationship with Russia represents a significant geopolitical shift with far-reaching implications. While the promise of economic support and strategic partnership is enticing, the risks associated with this realignment are substantial. Somalia’s leaders must navigate this transition with caution, ensuring that the nation’s long-term stability and development are prioritized.

By adopting a balanced and strategic approach, Somalia can leverage its newfound partnerships to build a more prosperous and stable future. The international community, meanwhile, must remain engaged, offering support and guidance to ensure that Somalia’s journey towards progress is both sustainable and inclusive.

Sources and References:

- World Bank

- EU Tax Observatory

- MIT Economics Department

- United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM)

- African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM)

- Interviews with Somali and international political analysts

For an exclusive, in-depth analysis of Somalia-Russia relations, stay tuned to waryatv.com.

UNSOM’s Demise: Somalia’s Descent into the Abyss of State Collapse

World Bank Issues Stern Warning to Somalia Over Audit Delays

Analysis

The Devastating Impact of Khat: A Comprehensive Analysis of Somaliland’s Crisis

Unveiling the Religious, Health, Economic, and Environmental Ravages of Khat Consumption in Somaliland

By Kasim Abdulkadir:

In the tranquil streets of Somaliland, an invisible enemy lurks, threatening the essence of society and corroding its foundations. This enemy is none other than Khat, a narcotic plant wreaking havoc on the religious, health, economic, moral, hygienic, and environmental spheres of Somaliland.

- Religious Problems of Khat: Khat’s insidious infiltration into the societal fabric of Somaliland has unleashed a myriad of religious challenges. The gluttonous consumption of Khat undermines the completeness of faith, diverting individuals from their religious obligations. Fasting, the cornerstone of religious practice, is undermined by Khat consumption, hindering individuals from fulfilling their sacred duties.

- Health Problems of Khat: The detrimental impact of Khat on public health cannot be overstated. From neurological impairment to digestive disturbances, Khat inflicts severe harm on the human body. Its consumption weakens the immune system, rendering individuals susceptible to illness and posing grave risks to their overall well-being.

- Financial Problems of Khat: Khat’s pervasive influence extends to the economic realm, paralyzing communities and draining resources. The economic paralysis induced by Khat consumption disrupts livelihoods and perpetuates cycles of poverty. Scarce financial resources are squandered on Khat, exacerbating economic inequalities and stifling progress.

- Moral Problems of Khat: In a society anchored in the principles of Islam, Khat engenders moral degradation, eroding the fabric of social cohesion. The vile behavior exhibited by Khat users stands in stark contrast to the moral virtues espoused by Islam, perpetuating discord and disharmony within communities.

- Hygienic Problems of Khat: Khat’s consumption fosters neglect of personal hygiene, exacerbating societal challenges and perpetuating unhygienic living conditions. The relentless pursuit of Khat leaves individuals devoid of the inclination to maintain cleanliness, further exacerbating public health concerns.

- Family Problems of Khat: The scourge of Khat precipitates familial discord, tearing apart the fabric of familial bonds and disrupting domestic tranquility. Marital strife, fueled by the financial strain of Khat consumption, destabilizes households and undermines familial cohesion.

- Environmental Problems of Khat: As Khat consumption proliferates, it exacts a heavy toll on the environment, polluting ecosystems and despoiling landscapes. The wanton disposal of Khat waste contaminates soil and disrupts natural habitats, threatening biodiversity and compromising environmental sustainability.

Conclusion: The pernicious influence of Khat permeates every facet of Somaliland society, leaving devastation in its wake. Urgent measures are imperative to combat this existential threat and safeguard the future of Somaliland. Only through concerted efforts to address the religious, health, economic, moral, hygienic, and environmental ramifications of Khat consumption can Somaliland reclaim its vitality and resilience.

The Poisoned Chalice: Battling the Khat Epidemic in Somaliland

In the face of adversity, Somaliland must unite to confront the scourge of Khat and forge a path towards renewal and prosperity.

Analysis

Ransom payment could trigger new wave of Somali pirate attacks

EU NAVFOR ATALANTA Warns of Potential Surge in Attacks

By Kasim Abdulkadir:

The European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR ATALANTA) has issued a stark warning about the potential for a resurgence in Somali pirate attacks, citing recent events and the end of the monsoon season as contributing factors. The threat of ransom payments, coupled with the hijacking of dhows used as motherships, poses a grave risk to shipping in the Western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden.

EU NAVFOR ATALANTA’s assessment underscores the dangerous dynamics at play. While there have been no recent piracy-related incidents, the payment of ransom for previously hijacked vessels could embolden pirate groups to escalate their activities. Hijacked dhows, disguised among regular shipping traffic, serve as launching pads for future attacks, potentially extending as far as 600 nautical miles from the Somali coast.

The surge in piracy incidents since November, including the hijacking of 18 dhows, indicates the persistence of the threat. Despite some vessels being released, others remain under pirate control, highlighting the continued operational capacity of pirate groups in the region. Recent suspicious approaches near the island of Socotra underscore the evolving nature of the threat.

EU NAVFOR ATALANTA estimates the presence of at least two pirate action groups operating off the Somali coast, emphasizing the need for heightened vigilance. The threat level is considered moderate, with the possibility of pirate attacks deemed realistic. Adherence to Best Management Practices (BMP5) recommendations is deemed crucial for vessels operating within 700 nautical miles of the Somali coast.

The warning serves as a reminder of the ongoing risks faced by maritime vessels traversing the Western Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. Heightened security measures, including the implementation of BMP5 guidelines, are essential for mitigating the threat posed by Somali piracy. Failure to adhere to these recommendations could leave vessels vulnerable to attack and hijacking.

In conclusion, EU NAVFOR ATALANTA’s alert underscores the precarious nature of maritime security in the region, with ransom payments potentially fueling a new wave of Somali pirate attacks. Vigilance, adherence to security protocols, and international cooperation are paramount in safeguarding shipping lanes and preventing further escalation of piracy incidents.

Corruption

EXPOSING: Somalia’s Corrupt Economy and Terrorist Ties

In a shocking revelation, Somalia has emerged as a hub for illicit financial activities, with millions of dollars being sent abroad by foreigners every month. This clandestine operation has raised serious concerns about the integrity of Somalia’s economy and its ties to terrorist organizations like Al-Shabab.

Reports indicate that a staggering $21 million is funneled out of Somalia annually, with Kenyan and Ugandan workers in the country playing a significant role in this scheme. Around 35,000 Ugandans alone are employed in Somalia, transferring between $50,000 and $60,000 daily. This influx of money has turned Somalia into a lucrative financial center for foreign nationals, exploiting its fragile economy and lax regulations.

Despite Somalia’s exclusion from recent remittance reports by the Central Bank of Kenya, it remains a hotspot for Ugandan workers seeking employment opportunities. The number of Ugandans in Somalia has surged since the establishment of joint relations between the two countries in August 2022, signaling a troubling trend of exploitation and financial manipulation.

Moreover, Somalia and its partners have painted a rosy picture of economic growth, boasting a projected GDP increase of 3.7% this year. However, this optimism is overshadowed by endemic corruption and government mismanagement, which hinder genuine economic progress and perpetuate poverty among the Somali people.

The removal of investment barriers by the Somali government may seem like a step in the right direction, but it only serves to facilitate further exploitation by foreign entities. While Prime Minister Hamsa Abdi Barre touts the Investment Protection Law as a tool to attract foreign investors, it is clear that Somalia’s economy remains vulnerable to exploitation and manipulation.

Furthermore, the passage of the Anti-Terrorism Law in 2023, ostensibly aimed at combating terrorism, has done little to curb the influence of terrorist organizations like Al-Shabab. Instead, it has provided a pretext for increased government surveillance and control, further stifling economic growth and dissent.

In light of these revelations, it is imperative for the international community to scrutinize Somalia’s financial activities and hold its leaders accountable for their complicity in corruption and terrorism. Failure to do so will only perpetuate Somalia’s status as one of the most corrupt and dangerous countries in the world, condemning its people to a future of poverty and instability.

Somalia

Who are Somalia’s al-Shabab?

Who are al-Shabab?

Al-Shabab means The Youth in Arabic.

It emerged as the radical youth wing of Somalia’s now-defunct Union of Islamic Courts, which controlled Mogadishu in 2006, before being forced out by Ethiopian forces.

There are numerous reports of foreign jihadists going to Somalia to help al-Shabab, from neighbouring countries, as well as the US and Europe.

It is banned as a terrorist group by both the US and the UK and is believed to have between 7,000 and 9,000 fighters.

Al-Shabab advocates the Saudi-inspired Wahhabi version of Islam, while most Somalis are Sufis.

It has imposed a strict version of Sharia in areas under its control, including stoning to death women accused of adultery and amputating the hands of thieves.

What drives al-Shabab?

What are its links to other jihadists?

In a joint video released in February 2012, then al-Shabab leader Ahmed Abdi Godane said he “pledged obedience” to al-Qaeda head Ayman al-Zawahiri.

There have also been numerous reports that al-Shabab may have formed some links with other militant groups in Africa, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, based in the Sahara desert.

Al-Shabab debated whether to switch allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) group after it emerged in January 2014.

It eventually rejected the idea, resulting in a small faction breaking away.

Al-Shabab is currently led by Ahmad Umar, also known as Abu Ubaidah.

The US has issued a $6m (£4.5m) reward for information leading to his capture.

Al-Shabab wants IS to back off

How dangerous is the group?

Somalia’s government blamed it for the killing of at least 500 people in a huge truck bombing in the capital Mogadishu in October 2017. It was East Africa’s deadliest bombing. Al-Shabab, however, did not claim responsibility for it.

It did confirm carrying out a massive attack on a Kenyan military base in Somalia’s el-Ade town in January 2016, killing, according to Somalia’s then-President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, about 180 soldiers. The Kenyan military disputed the number, but refused to give a death toll.

It has also staged several attacks in Kenya, including the 2015 massacre at Kenya’s Garissa University, near the border with Somalia.

A total of 148 people died when gunmen stormed the university at dawn and targeted Christian students..

In 2013, its gunmen stormed the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi, resulting in a siege which left at least 67 people dead.

During the 2010 football World Cup final between Spain and the Netherlands, it bombed a rugby club and a restaurant in Uganda’s capital Kampala, killing 74 people watching the match.

How much of Somalia does al-Shabab control?

Although it has lost control of most towns and cities, it still dominates in many rural areas.

It was forced out of the capital, Mogadishu, in August 2011 following an offensive spearheaded by about 22,000 African Union (AU) troops, and left the vital port of Kismayo in September 2012.

The loss of Kismayo has hit al-Shabab’s finances, as it used to earn money by taking a cut of the city’s lucrative charcoal trade.

The US has also carried out a wave of air strikes, which led to the killing of the group’s leader, Aden Hashi Ayro, in 2008 and his successor, Ahmed Abdi Godane.

In March 2017, US President Donald Trump approved a Pentagon plan to escalate operations against al-Shabab.

The US has more than 500 troops in Somalia and conducted 30 airstrikes in 2017, more than four times the average number carried out in the previous seven years, according to The Washington Post.

Although the military operations are weakening al-Shabab, the group is still able to carry out suicide attacks and has regained control of some towns.

The AU is reducing its troop presence – about 1,000 have left and a further 1,000 are due to leave in 2018.

This follows a cut in funding by the European Union (EU), amid allegations of corruption within the AU force, made up of troops from Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti.

What is happening in Somalia?

Somalia has not had an effective national government for more than 20 years, during which much of the country has been a war-zone.

Al-Shabab gained support by promising people security. But its credibility was knocked when it rejected Western food aid to combat a 2011 drought and famine.

With Mogadishu and other towns now under government control, there is a feeling of optimism and many Somalis have returned from exile, bringing their money and skills with them.

Basic services such as street lighting, dry cleaning and rubbish collection have resumed in the capital.

But Somalia is still too dangerous and divided to hold democratic elections – the last one was in 1969.

So, its parliament and president are elected through a complex system, with clan elders playing an influential role in the process.

-

Editor's Pick4 months ago

Editor's Pick4 months agoEmpowering Africa’s Economic Future: The Significance of the Digital Trade Protocol

-

Crime4 months ago

Crime4 months agoSomali USA Gangs: Deadly Twist in Shocking St. Paul Shooting

-

Analysis4 months ago

Analysis4 months agoNavigating the Age of Amorality: America’s Dilemma in Upholding the Liberal Order

-

Top stories3 months ago

Top stories3 months agoExposing Somalia’s Crisis: The Chairman’s Concerns and Calls for Action

-

Crime3 months ago

Crime3 months agoA Child’s Confession: 10-Year-Old Texas Boy Claims Responsibility for Killing Man Two Years Ago

-

Top stories3 months ago

Top stories3 months agoTrump’s Comparisons: Charlottesville Rally and Israel Protests

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoFrom Folded to Freedom: The Journey of the ‘World’s Most Folded Man

-

Analysis3 months ago

Analysis3 months agoSadiq Khan Secures Historic Third Term as London Mayor Amidst Political Tensions